A History of Slavery in Carroll County, MD

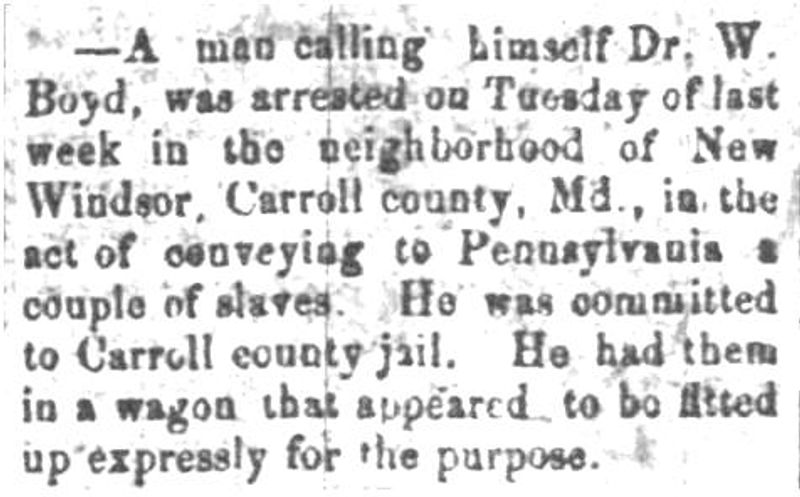

From its beginning, in the 1660’s, Maryland’s population was religiously, socially and racially diverse. Indentured laborers, mostly white, dominated the Maryland workforce throughout the 17th century. Unlike the Virginians, the Maryland colonists brought Africans with them, and as European servants became scarce and expensive, African labor came to dominate the labor force. Legislation at that time slowly sealed the fate of African immigrants and their descendants by removing opportunities for freedom and advancement, and by 1710, the number of enslaved Africans had increased to 3500, making up about 24% of the population - most were still “country-born,” that is born in Africa, and most were men. Between 1700 and 1780, new generations of African people born in the Maryland colony expanded the enslaved population. By law, Africans, with the exception of those entering the Eastern Shore, entered the colonies as slaves for life. Even if they were freed, their freedoms were inhibited by laws that left them few liberties. During this time, at least half of Maryland’s enslaved population lived in Calvert, Charles, Prince George’s, and St. Mary’s counties, as these counties had the largest crops of tobacco in the state. The other enslaved populations lived in Annapolis and Baltimore.1 Although the practice of slavery wasn’t as prominent in Carroll County as it was in other areas, the brutality of the system was all too real. According to a census taken in 1840, three years after the founding of Carroll County, there were 1,044 slaves residing here, mostly in the southern part of the county where farms were larger and grew labor-intensive crops like tobacco. Not much is known about this population of slaves as a whole; only what is to be gleaned from the old records from the era, inventories that listed the ownership of slaves the way one would claim ownership of a mule, manumission papers and books containing certificates of freedom, which essentially acted as passports for freed African Americans. Many slaves were granted freedom by their masters’ wills, others won their freedom by serving in the U.S. Colored Troops during the Civil War, and others found ways to purchase their freedom. Throughout the decade of the 1850s, mid-Marylanders and their near-by neighbors in Pennsylvania and Virginia found themselves trying to navigate a path through the increasingly tense sectional disagreements between the North and the South. Mid-Marylanders, including those in Carroll County, had extensive ties – politically, economically, and socially – with both sides of the impending Civil War, and during this time the enslaved populations in the counties of Carroll, Frederick, and Washington numbered almost 7,000, making up 8% of the total population. This was much less than bordering counties such as Loudan (VA) and Jefferson (WV) who had close to 10,000 slaves, which made up 27% of their populations. Still, slavery was a growing issue for citizens on both sides of the Mason-Dixon Line who had already confronted the issue of slavery repeatedly, both directly and indirectly. By 1860, according to a “Map showing the distribution of the slave population of the southern states of the United States. Compiled from the census of 1860.” (Library of Congress), African Americans in mid-Maryland and the surrounding region varied. Slavery in mid-Maryland had been declining since 1820: in 1820 over 16% of the total population of Frederick County was enslaved; by 1860 that number had dropped to 7%. The same pattern was true for Washington County, which went from 14% enslaved in 1820 to 5% in 1860. In Carroll County, created in 1837, only 3% of its residents were enslaved by the time of the Civil War. A prominent historian has argued that in this wheat-producing interior of the state, a way of life was developing in which slavery was “tangential.” Yet these diminishing numbers are in some ways misleading with regard to slavery’s significance in the region, for slavery persisted in exerting its influence politically and socially despite its decline. Mid-Maryland was not economically dependent on slavery, but it did have an investment in the institution.2 In 1859, John Brown’s Harpers Ferry Raid galvanized public opinion on the issue of slavery, and Maryland was not without its conflicts. Marylanders were authorized to “arrest and detain” suspicious persons who fraternized with John Brown’s anti-slavery ideas, and they hired extra deputies to assist with the process. In New Windsor, in Carroll County, a Dr. W. Boyd was arrested for trying to smuggle out of Maryland several slaves into Pennsylvania who were hidden in a secret compartment he had made in his wagon. For his effort, Dr. Boyd was captured and incarcerated in the Carroll County jail. 3 Neither the preliminary announcement of emancipation released on September 22, 1862, nor the official Emancipation Proclamation of January 1, 1863 freed a single slave in Maryland. The Civil War raged on through its foothills and valleys, with casualties including those of freed slaves who were inspired by the Proclamation to enter the service to fight for the Union. Because President Abraham Lincoln’s policy only affected states in rebellion, abolition was delayed in Maryland until a new state constitution went into effect in November 1864. Votes from Maryland’s Union soldiers at the front were a deciding factor in passing the referendum. Local historians uncovered evidence of a number of the African-American communities that cropped up after the Civil War. Some of them exist to this day, but others are only remembered by notations on old maps. As one historian noted, “Maps from 1862 and 1877 preface the names of schools with the word “colored,’ [which gave] a hint as to where these pockets of African-Americans really were at the time.” Some of the oldest African-American communities in the county lie in the Union Bridge area, McKinstry’s Mill area and Bark Hill Road area. African-American communities in the southern part of the county, particularly the Sykesville area, were established by freed slaves. Their legacy is remembered in a one-room schoolhouse located on Main Street. The Old Colored Schoolhouse was built in 1903 at the request of area African-Americans and operated from 1904 to 1938, when the county approved a consolidation plan for the county’s “colored” schools. Today, the schoolhouse has been restored to its 1904 appearance and serves as a museum, a monument to man’s quest for learning in an era of racism and segregation.4

Work cited:

1. National Park Service, African American Heritage, Department of Interior (2025). NPS Ethnography, The Peopling of the Maryland Colony. https://www.nps.gov/ethnography/aah/aaheritage/chesapeakeb.htm#:~:text=During%2 0this%20time%2C%20at%20least,Mary's%20counties. 2. Article: The Crossroads of War and Freedom (2024). The Coming Storm. https://crossroadsofwar.org/discover-the-story/the-coming-storm#:~:text=Slavery%20an d%20Freedom%20in%201860&text=African%20Americans%20in%20mid%2DMaryland,a n%20investment%20in%20the%20institution. 3. Emily Huebner. (2025). Bugle Call. Heart of the Civil War, Blog. https://www.heartofthecivilwar.org/blog/researching-stories-of-slavery-in-familiar-lands capes 4. Patricia Bianca. (2007) Carroll County Magazine. A History of Strength and Determination. https://carrollmagazine.com/a-history-of-strength-and-determination/ 5. Enoch Pratt Free Library Special Collections. (2017) Carroll County Historical Records. https://www.prattlibrary.org/assets/documents/locations-and-hours/ms-41-guide-to-ca rroll-county-historical-documents.pdf

5.0 (11 Reviews)

Downtown Sykesville Connection

7566 Main Street, Suite 302

Sykesville, MD 21784

(410) 216-4543

www.downtownsykesville.com

Mon, Tue, Wed, Thu, Fri, Sat10:00am-10:00pm